Equine strangles is one of the most common infectious diseases affecting horses worldwide. While many cases resolve with proper care, strangles’ highly contagious nature makes it a serious concern for boarding barns, training facilities, showgrounds, and private horse owners. A single case can quickly escalate into a full-blown outbreak if biosecurity measures are not implemented immediately and consistently.

It’s important to learn how strangles spreads, what you can do to prevent your horse from coming into contact with it, and how to implement sound biosecurity protocols if you find yourself in an outbreak.

What Is Equine Strangles?

Strangles is a bacterial infection caused by Streptococcus equi subspecies equi. The bacteria target the upper respiratory tract and lymph nodes, particularly those under the jaw and around the throatlatch. The disease gets its name from the severe swelling that can occur in these lymph nodes, which in extreme cases can interfere with breathing.

Strangles most commonly affects young horses, but any horse, regardless of age, breed, or discipline, can become infected. Horses that travel frequently, live in close quarters with others, or are exposed to new arrivals face a higher risk. Sale barns, livestock transporters, even high traffic show barns can all be hot spots.

How Strangles Spreads

Strangles is extremely contagious and spreads through both direct and indirect contact.

Direct Transmission

- Nose-to-nose contact with an infected horse

- Exposure to nasal discharge or pus from abscesses

Indirect Transmission

- Shared water buckets, troughs, or hoses

- Feed tubs and hay nets

- Grooming tools, tack, blankets, and saddle pads

- Trailers, stalls, fences, and cross-ties

- Human hands, clothing, footwear, and equipment

The bacteria can survive for weeks, sometimes months, in moist environments. Horses that appear fully recovered may even continue shedding bacteria, becoming “silent carriers” that can spark future outbreaks without obvious warning.

Signs and Symptoms of Strangles

The incubation period for strangles ranges from 3 to 8 days. At this point, you may see clinical signs appear. Fever is often the earliest and most reliable indicator, making daily temperature monitoring critical in high-risk situations.

Symptoms include:

- Fever (> 103F)

- Lethargy and depression

- Loss of appetite

- Nasal discharge that becomes thick, yellow, or pus-like from one or both nostrils

- Swollen lymph nodes under the jaw or throatlatch

- Abscess formation that may rupture and drain

- Difficulty swallowing

- Labored or noisy breathing in severe cases

Some horses (usually older or previously exposed horses) show only mild symptoms, while others develop severe swelling and discomfort. A small percentage may never show obvious signs but still spread the bacteria.

Diagnosis and Veterinary Care

If strangles is suspected, contact a veterinarian immediately. Early confirmation allows for faster isolation and reduces spread.

Diagnosis typically involves:

- Nasal swabs or washes

- Sampling of abscess material

- PCR testing for Streptococcus equi

Treatment varies depending on the stage and severity of infection. Many horses recover with supportive care alone and develop immunity that lasts around 5 years.

Other treatment interventions include:

- Rest and isolation

- Soft or soaked feed to ease swallowing

- Anti-inflammatory medications

- Warm compresses to encourage abscess maturation and drainage

Antibiotics are sometimes used in early cases or severe infections but are often avoided once abscesses have formed, as they may delay natural immunity.

A Detailed Biosecurity Protocol for Strangles

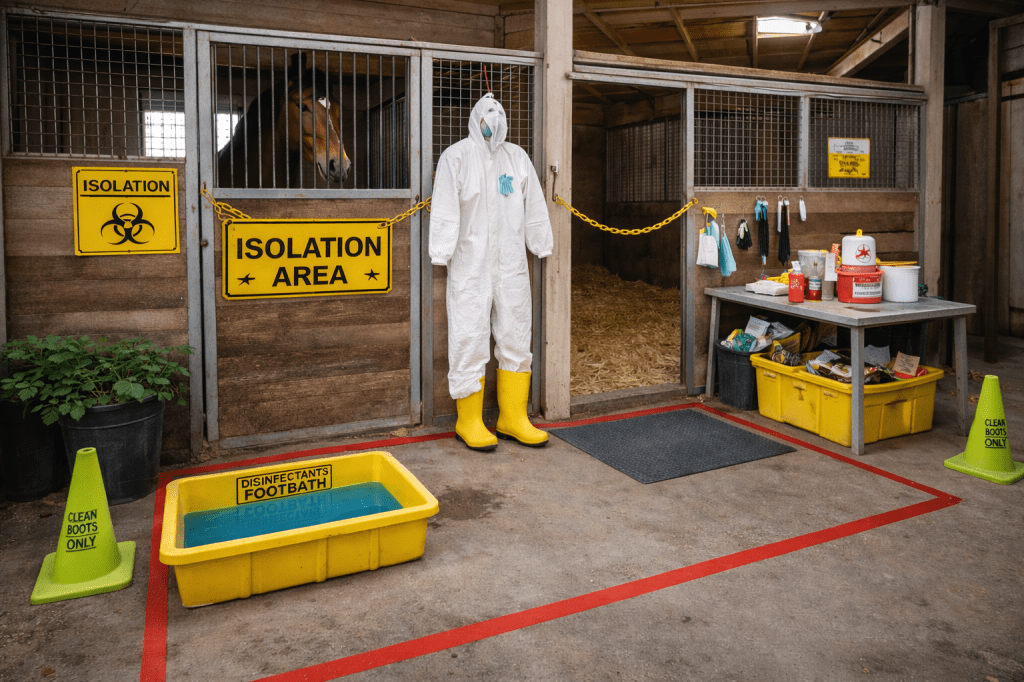

Effective biosecurity is the single most important factor in controlling and preventing strangles outbreaks. These protocols should be implemented immediately when strangles is suspected.

Some barn owners automatically implement strict quarantine and biosecurity measures for any new horses on the property (such as new boarders), regardless of symptoms, for 10-14 days as an extra measure of precaution against strangles and other infectious diseases.

1. Immediate Isolation

- Separate (at least 15-20 feet or more) infected horses from all others at the first sign of fever (over 101.5F) or nasal discharge

- Use a designated isolation area far from main traffic zones

- Designate a dress in/out and footbath zone, or establish a perimeter if using a stall for humans to divert around

- Do not allow shared airspace if possible

2. Grouping Horses by Risk Level

It can be helpful to divide horses into three groups, if you’re at a larger barn, to organize chores and cleaning routines:

- Red Group: Confirmed infected horses

- Amber Group: Exposed horses with no symptoms

- Green Group: Unexposed horses

Care for horses in this order:

- Green (healthy)

- Amber (exposed)

- Red (infected)

Never move backward through groups without changing clothes and disinfecting (it’s like touching raw meat, then every utensil in your utensil drawer, then washing your hands. Gross.)

3. Dedicated Equipment

- Assign separate buckets, feed tubs, halters, lead ropes, grooming tools, and mucking equipment to each group

- Color-coding equipment can help prevent mix-ups

- Never share water hoses or sponges between groups

4. Human Hygiene and Protective Measures

- Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water between handling horses

- Use disposable gloves when handling infected horses

- Put on a Tyvek suit (or coveralls and a hair bonnet), and designated rubber boots after working through the “green” group, and before entering the “amber” group.

- Disinfect footwear using footbaths with appropriate disinfectants (a 1:10 part bleach bath does the trick)

- Remember to change out the bleach water each time you have to use it. Bleach becomes inactivated when it encounters organic material (like dirt), and the bleach will evaporate out of the dilution within 24 hours.

5. Cleaning and Disinfection

Effective disinfectants include:

- Chlorhexidine

- Iodine-based solutions

- Accelerated hydrogen peroxide

- Bleach (used correctly and safely)

Key points:

- Clean organic matter off surfaces (manure, dirt, discharge) before disinfecting them

- Allow proper contact time for disinfectants to work

- Focus on high-touch surfaces like gates, stall doors, cross-ties, and hoses

6. Water and Feeding Protocols

- Eliminate shared water sources immediately

- Dump and disinfect buckets daily

- Use individual feed containers

- Do not allow horses to drink from communal troughs

7. Monitoring and Record-Keeping

- Take temperatures daily for all horses on the property

- Keep written logs of temperatures, symptoms, and treatments

- Continue monitoring for at least 21 days after the last clinical case

8. Quarantine for New Arrivals

Even outside of outbreaks, quarantine is essential:

- Isolate new horses for 10-14 days

- Monitor temperatures daily

- Use separate equipment

- Avoid nose-to-nose contact

This practice alone can prevent many outbreaks.

Vaccination Considerations

Strangles vaccines are available but not recommended universally. Vaccination decisions should be made with your veterinarian based on:

- Travel frequency

- Boarding or show exposure

- Previous outbreaks

- Age and immune status

Vaccines may reduce severity but do not guarantee prevention, and some horses experience adverse reactions.

Potential Complications from Strangles

Most horses recover uneventfully, but complications can occur, including:

- Bastard strangles: Abscesses in internal organs

- Purpura hemorrhagica: Immune-mediated swelling and bleeding

- Persistent carriers: Horses that continue shedding bacteria long-term

Prompt veterinary care and proper biosecurity significantly reduce these risks.

Recovery and Returning to Normal Operations

A barn should not resume normal operations until:

- All horses are symptom-free

- Follow-up testing confirms no active shedding

- Isolation areas are fully disinfected

- Veterinarian approval is obtained

Rushing this process increases the risk of reinfection and future outbreaks.

Common Sense Goes a Long Way

Equine strangles is stressful, inconvenient, and sometimes frightening, but it is manageable. Keep an eye on horses coming and going, isolate if any are symptomatic, and communicate with your vet. Follow their instructions and use common sense to prevent cross-contamination.